Kochi of the

sixties permitted no beginnings, no ends.

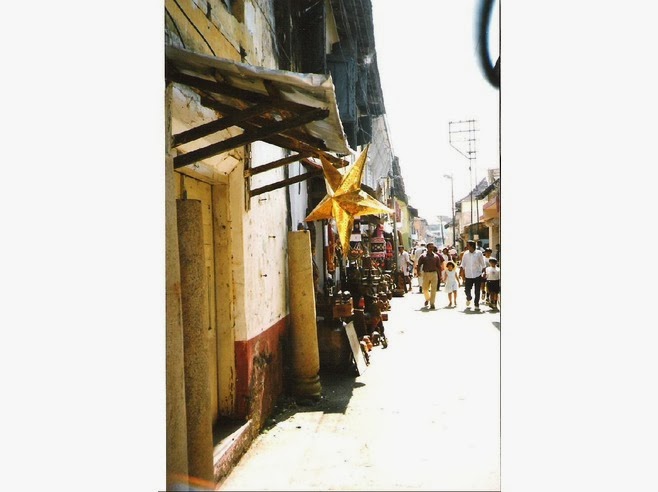

Bulk of the commerce

in the city was transacted within a rectangular piece of land bordered by M.G.

Road on the east, Banerji Road on the north, Shanmugham Road on the west and

Durbar Hall road on the south. This block of land accommodated the Central

Market, principal shopping centres and commodity business houses along Cloth

Bazar Road, Jews Street, Market Road and several smaller roads where traders of

different faiths offered commodities and services of all sorts to the buyers.

No one kew where Jews

Street started; at Pullepady junction or at Padma junction or at Flower

junction but the street ended no where. The westward stretch from Flower

junction, however, was crowded with dirty puddles all along and hardware

vendors on both sides. Steel traders from outside the State set up their

offices there; one of them, a steel manufacturer from Mahadevapura in

Bangalore, had its office on the first floor of a shabby building. A wooden

staircase in poor state of repairs led to their office.

In the seventies, a

young lad from Thrissur joined the steel company, immediately after his

graduation from Kerala Varma College, as office manager. The diligent young man steadily broadened the business and

positioned his company as a strong competitor to the established steel traders.

Soon the shrewd man realised he had opportunities to make a fast buck by making

the most of his status as the depot manager and, with the help of a few friends,

embarked on a tour of embezzlement. He

opened many bogus companies and brought truck loads of steel to sell in the

local market evading central sales tax. Every evening, his office desk would be

filled with cash as he was unable to use normal banking services due to the

grey nature of his business.

Sivaraman, one of his

acquaintences on whose name he had opened a bogus company, knew about the cash

stored in office. One evening, Sivaraman visited the office in company of an

accomplice, slashed the manager with a country sword and escaped with lakhs of

rupees stored there. Anil Kumar survived the attack though, but with serious

injuries.

A few shops away from

the steel company’s office was a hardware store. Lawrence, a young hardware

merchant, hailed from a wealthy business

family in Kunnamkulam which owned many hardware shops in central and north

Kerala. Born with a silver spoon in his mouth, the youth had extravagent

tastes. Soon he fell in love with a penniless counter girl at a travel agency

which shocked his orthodox family. They disowned the prodigal son and banished

him from home and the family businesses. With no resources to fall back on, the

young man turned to fraudulent deals to be eventually caught by law and ended up in jail.

Travelling north from

Shenoy’s cinema, one entered a small junction which hosted a famous tailoring

shop, Byblos, owned by Antony, Antho to his friends, a favorite place for most

of the youngsters, particularly girls. Antho started his career in Bahrain and

returned to Kochi in the seventies to work in his brother’s tailoring shop,

Thara Tailors, where he paraded his couture skills, first on himself and later

on his young customers whose number grew by the day. Later, gathering a small

capital together, Antho started his first own venture, Fila Tailors, near

Kacheripady. The ambitious young man soon moved his business to a larger place,

renamed his business as Byblos and opened a branch in Palarivattom, bringing in

a partner to his business. The first setback of his career was waiting for

him there. A few unintelligent business decisions and a break up with his

partner saw the man in heavy debt, forcing him to move to Al Ain in the U.A.E.,

looking for greener pastures and ways to pay off the debts that seemed to pile

up with time.

A few years of hard

work in Al Ain and his innate enterprise helped him to save enough money to

clear the debts. Antony, the ever smiling handsome dude, is now happy managing

his new fashion business, a few steps away from his old shop, Byblos.

In 1947, as India was

gathering itself to embrace freedom from colonial rule, a young man was

planning his future. He opened a small textile shop in Cloth Bazar Road,

specialising in silk sarees. The shop was so small that there were no pieces of

furniture, the sales girls sat on floor mats and the buyers stood on the

pavement selecting the goods of their choice. Exclusivity of their stocks and

the smiling countenance of the owner attracted the upper class women by hoards

to the store and business soared. Jayalakshmi Silks, the textile major with

many huge outlets all over Kerala, had its humble beginnings at that narrow

selling space.

Years have transformed

Kochi into an aspiring metropolitan city but denuded it of the grace it once

had. The frenetic pace of professed progress has made life complex and

difficult. The trees that hovered as a canopy over the wild celebrations of a

Santhosh Trophy victory have been shaved off to accommodate the metro rail

project, wiping off the memories of a generation along with it. The massive escalation in the number

of buildings, a lot more than the frail roads could handle, has clogged the

city’s arteries. The stench of excrement at Kaloor junction is now replaced

with the disgusting odour of gasoline, a pollutant of higher order. The open lands

where boys played games of varied sorts have disappeared, ugly structures have taken

roots in their places. The omnipresence of garbage, but, remains.

We have lost the Kochi

of Antony and Lawrence and Anil Kumar the way we lost the multiplication tables

to the calculating machines, the way the fragrance of the flowers leaves the man whose

nose has been put under the surgical knife; Kochi has been shorn of its purity.

Life is not pure or simple any longer.

No comments:

Post a Comment